THE HISTORY OF EAST ASIAN CALLIGRAPHY

East Asian brush calligraphy closely integrates aspects of art, communication, and symbology, thus offering educators a particularly rich set of resources from which to draw upon. In this article, we start with an overview of brush calligraphy, including its relationship with art, communication, and symbology. We follow with a brief discussion of the historical and contemporary place of brush calligraphy in East Asian education and society; finally, we explore some pragmatic aspects of creating class sessions or even a course on brush calligraphy.

As an artistic genre, brush calligraphy holds a central place in the cultural history in East Asia. The form of the characters used in the Chinese writing system—as well as the other writing systems that were derived from it— have long held a place of special regard in the aesthetic traditions of the region. Brush calligraphy has historically been ubiquitous in the visual culture of China, Japan, and Korea, either as a complement to another kind of image (perhaps a landscape painting or part of an illustrated book) or as a work of art in its own right; consequently, it is central to the study of East Asian art history.

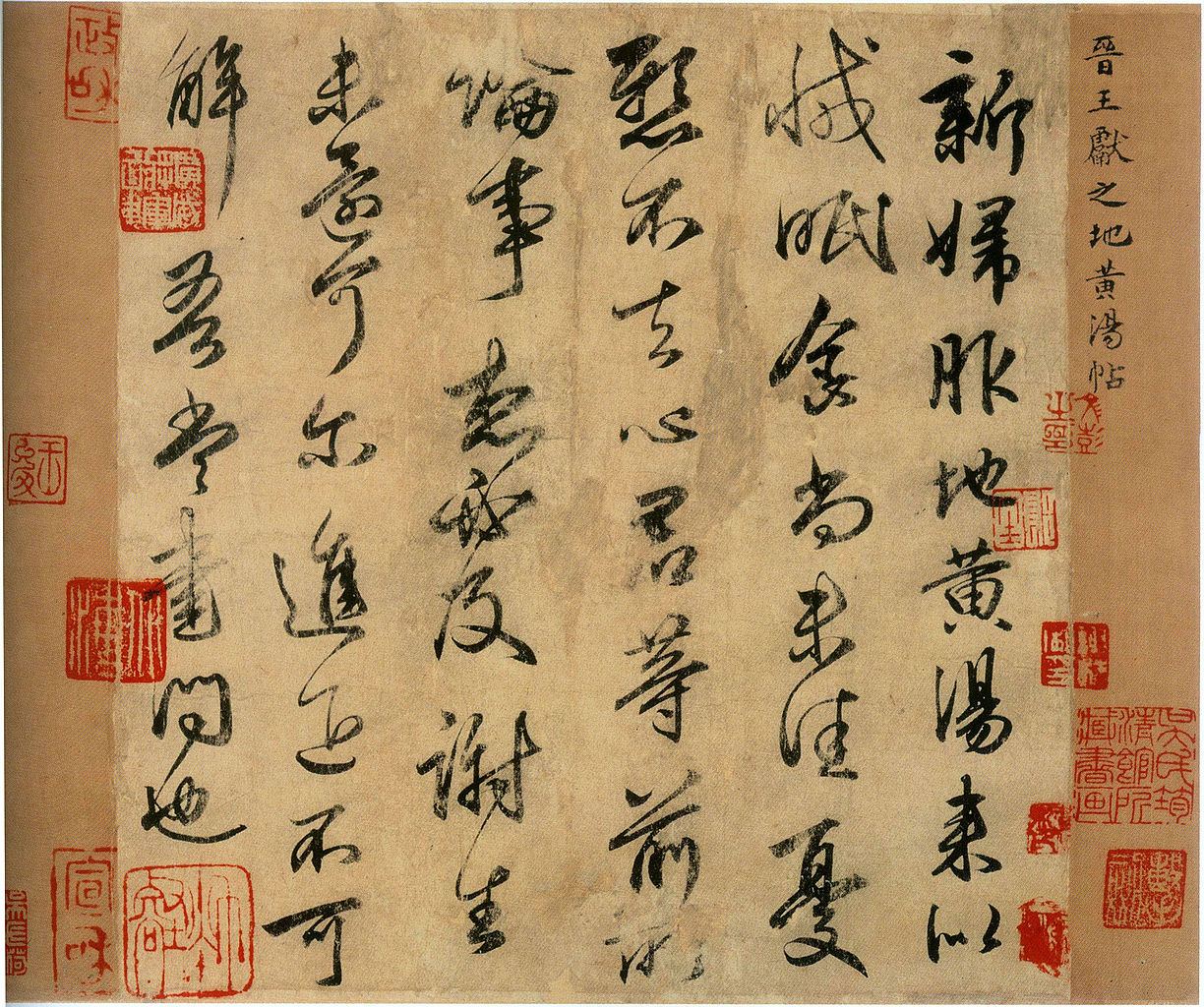

Chinese calligraphy reached its zeniths during the Jin and Tang Dynasties. Tang Dynasty in particular is praised as the golden age of Chinese culture, with calligraphy as one of its crowning achievements. In the Tang Dynasty the government set up academies for studying calligraphy. Calligraphy was used to asses the talents of a person and was considered as a way for selecting promising candidates.

Chinese calligraphy has been divided into five major styles: Zhuan Shu (篆书); which today mostly confined to seal carving, Li Shu (隶书); which is the traditional official style and was mainly dominated the calligraphy style of the Han Dynasty in 206 B.C.-220 A.D, Kai Shu (楷书); which was the most common form of printing, and also constitutes the standard form of Chinese’ writing, Xing Shu (行书); which is the most commonly used form of hand writing also known as ‘running style’ and finally Cao Shu (草书), the Chinese cursive style, mostly used by calligraphers for highly abstract works but also seen in everyday use. All these major forms can be divided further in various sub categories. There are also two earlier styles which are no more in common use and were not originally executed by brush, namely, the Jia Guwen ( 甲骨文) or “oracle bone script” and the Jin Wen (金文) which were characters engraved on bones, shells and bronze, sometimes categorized under Zhuan Shu.

EAST ASIAN ALPHABET

Chinese characters are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese.Chinese characters are the oldest continuously used system of writing in the world. By virtue of their widespread current use throughout East Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as their profound historic use throughout the Sinosphere, Chinese characters are among the most widely adopted writing systems in the world by number of users.

The total number of Chinese characters ever to appear in a dictionary is in the tens of thousands, though most are graphic variants, were used historically and passed out of use, or are of a specialized nature. A college graduate who is literate in written Chinese knows between three and four thousand characters, though more are required for specialized fields.

In Japan, 2,136 are taught through secondary school (the Jōyō kanji), and hundreds more are in everyday use. Due to separate simplifications of characters in Japan and in China, the kanji used in Japan today has some differences from Chinese simplified characters in several respects. There are various national standard lists of characters, forms, and pronunciations.

Simplified forms of certain characters are used in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia; traditional characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. In addition, Chinese characters have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as kanji.

Chinese characters in South Korea, which are known as hanja, retain significant use in Korean academia to study its documents, history, literature and records.

Vietnam once used the chữ Hán and developed chữ Nôm to write Vietnamese before turning to a romanized alphabet.

In Japan, common characters are often written in post-Tōyō kanji simplified forms, while uncommon characters are written in Japanese traditional forms. During the 1970s, Singapore had also briefly enacted its own simplification campaign, but eventually streamlined its simplification to be uniform with mainland China.

In modern Chinese, most words are compounds written with two or more characters. Unlike alphabetic writing systems, in which the unit character roughly corresponds to one phoneme, the Chinese writing system associates each logogram with an entire syllable, and thus may be compared in some aspects to a syllabary. A character almost always corresponds to a single syllable that is also a morpheme.However, there are a few exceptions to this general correspondence, including bisyllabic morphemes (written with two characters), bimorphemic syllables (written with two characters) and cases where a single character represents a polysyllabic word or phrase.

Modern Chinese has many homophones; thus the same spoken syllable may be represented by one of many characters, depending on meaning. A particular character may also have a range of meanings, or sometimes quite distinct meanings, which might have different pronunciations. Cognates in the several varieties of Chinese are generally written with the same character. In other languages, most significantly in modern Japanese and sometimes in Korean, characters are used to represent Chinese loanwords or to represent native words independent of the Chinese pronunciation (e.g., kun'yomi in Japanese). Some characters retained their phonetic elements based on their pronunciation in a historical variety of Chinese from which they were acquired. These foreign adaptations of Chinese pronunciation are known as Sino-Xenic pronunciations and have been useful in the reconstruction of Middle Chinese.

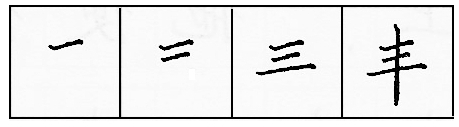

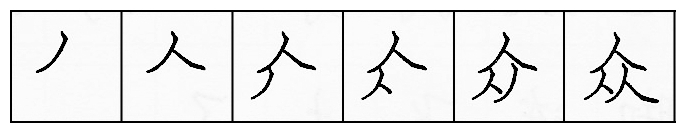

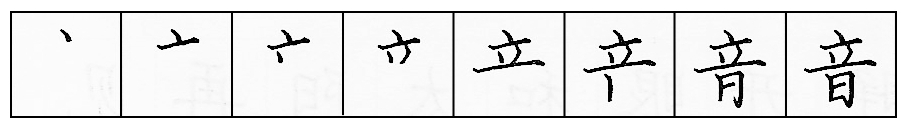

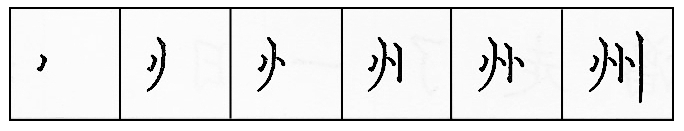

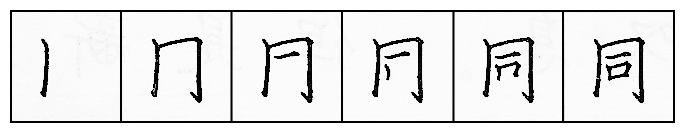

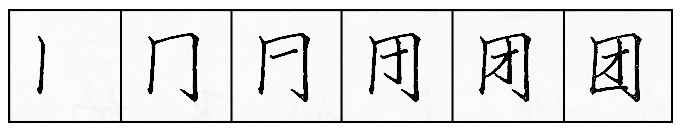

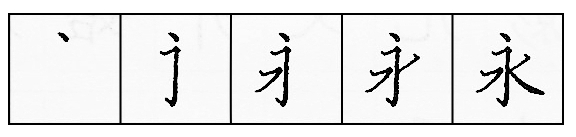

Here are the seven basic rules of stroke order in a Chinese character:

1.Draw horizontally then vertically

2.Draw the line down to the left and then down the right.

3.Write downward

4.Write from left to right

5.Trace the external strokes before interior strokes

6.Close after filling the frame

7.When a character is symmetrical, tracing the line of the middle first

8.The Chinese character is written in an imaginary square, without fully completing the square

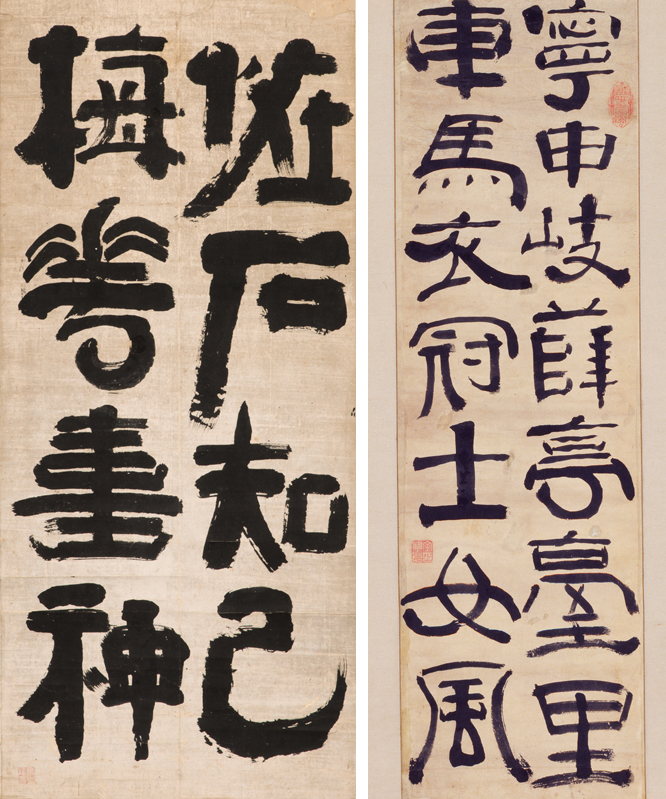

Calligraphy works by Kim Jeong Hui (1786-1856), a calligrapher during the Joseon Dynasty

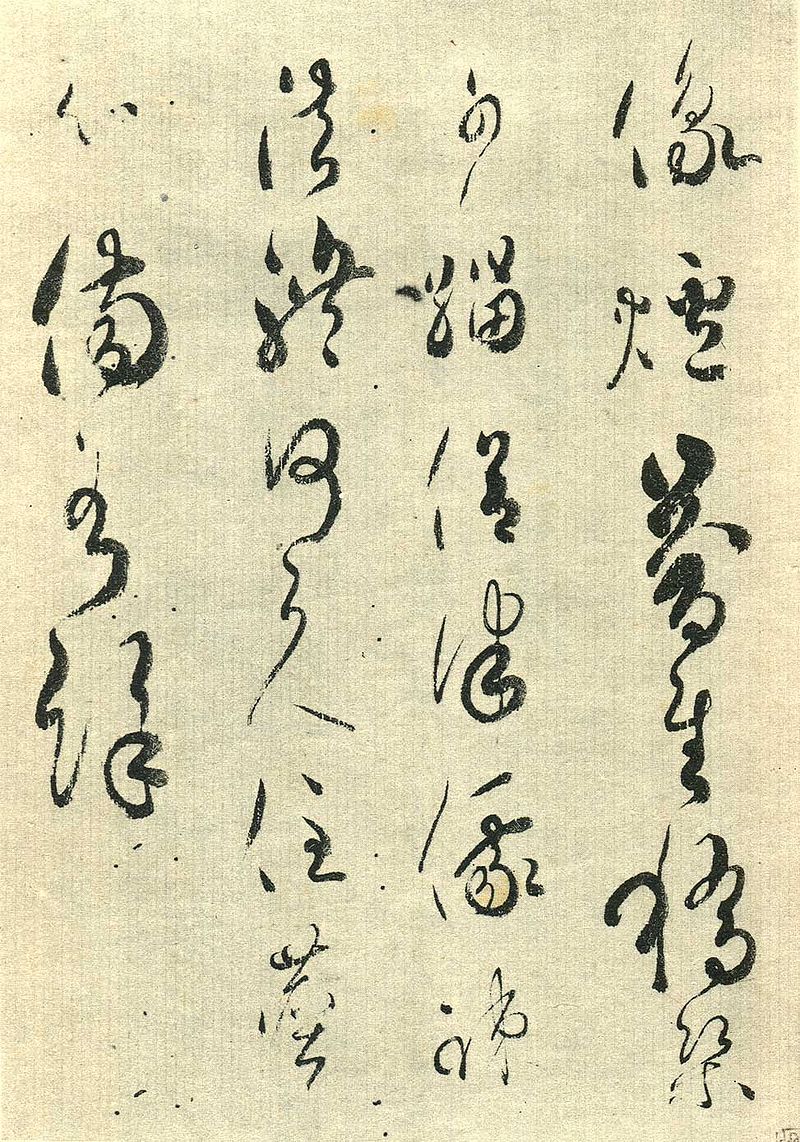

Cry for noble Saichō (哭最澄上人), written by Emperor Saga

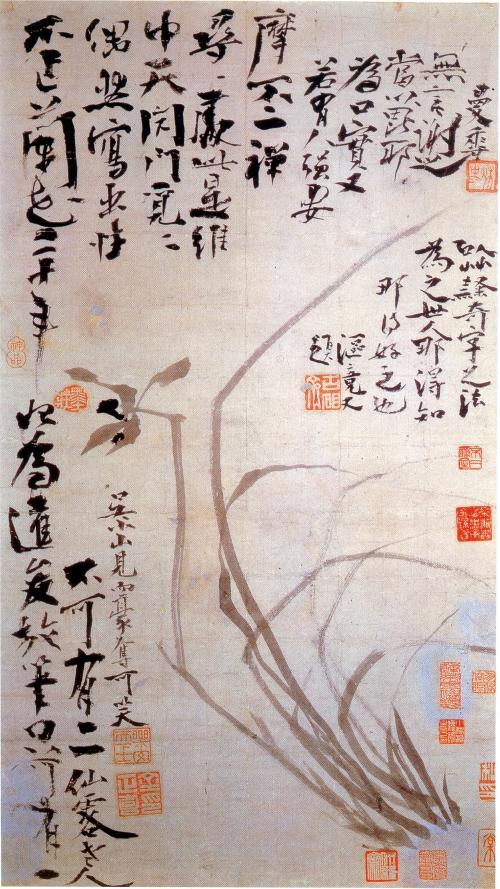

Buiseonrando, which was written and painted by Kim Jeonghee

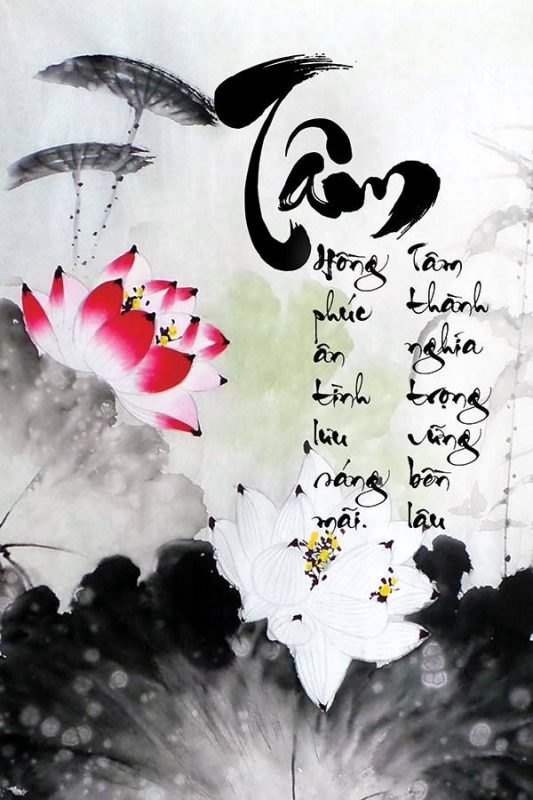

Vietnamese poetic calligraphy about the world's soul