THE HISTORY OF GREEK CALLIGRAPHY

Greek alphabet, writing system that was developed in Greece about 1000 BCE. It is the direct or indirect ancestor of all modern European alphabets. Derived from the North Semitic alphabet via that of the Phoenicians, the Greek alphabet was modified to make it more efficient and accurate for writing a non-Semitic language by the addition of several new letters and the modification or dropping of several others. Most important, some of the symbols of the Semitic alphabet, which represented only consonants, were made to represent vowels: the Semitic consonants ʾalef, he, yod, ʿayin, and vav became the Greek letters alpha, epsilon, iota, omicron, and upsilon, representing the vowels a, e, i, o, and u, respectively. The addition of symbols for the vowel sounds greatly increased the accuracy and legibility of the writing system for non-Semitic languages.

Before the 5th century BCE the Greek alphabet could be divided into two principal branches: the Ionic (eastern) and the Chalcidian (western). Differences between the two branches were minor. The Chalcidian alphabet probably gave rise to the Etruscan alphabet of Italy in the 8th century BCE and hence indirectly to the other Italic alphabets, including the Latin alphabet, which is now used for most European languages. In 403 BCE, however, Athens officially adopted the Ionic alphabet as written in Miletus, and in the next 50 years almost all local Greek alphabets, including the Chalcidian, were replaced by the Ionic script, which thus became the Classical Greek alphabet.

GREEK ALPHABET

Greek Majuscule:

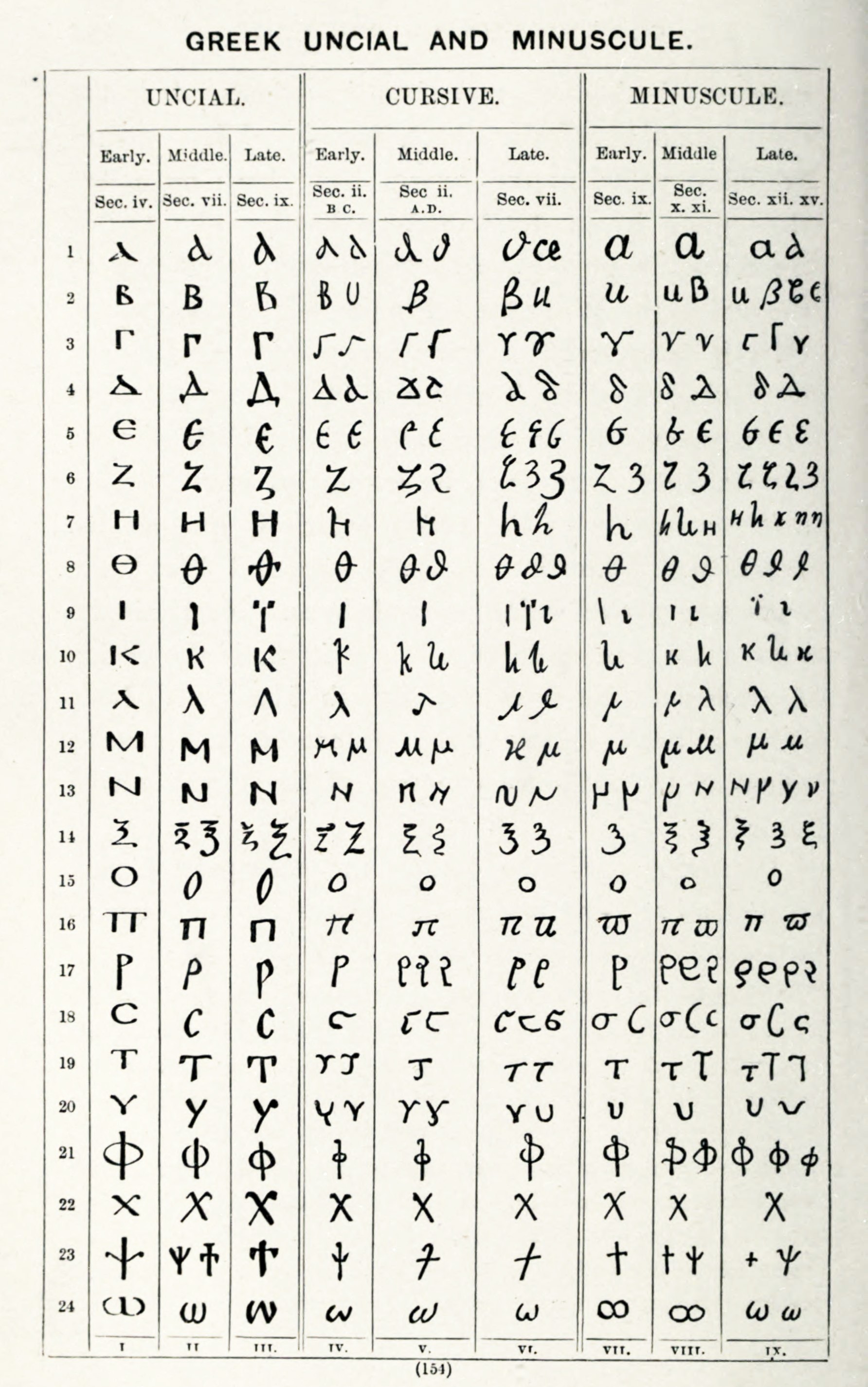

It may be surprising to know that the printed Greek found in textbooks and Greek New Testaments looks considerably different than the Greek penned by scribes more than a millennium ago. This handwritten Greek was produced in two stages and two distinctly different forms. These forms are known today as “majuscule” and “minuscule“. Majuscule Greek was written in a bilinear format, or what we might consider capital letters, with the top of each letter reaching to an imaginary, overhead ruling line and the base of the letter resting on the lower ruling line. These letters were also written in scriptio continua—meaning without spaces between words—with separate strokes and no connecting points between each letter.

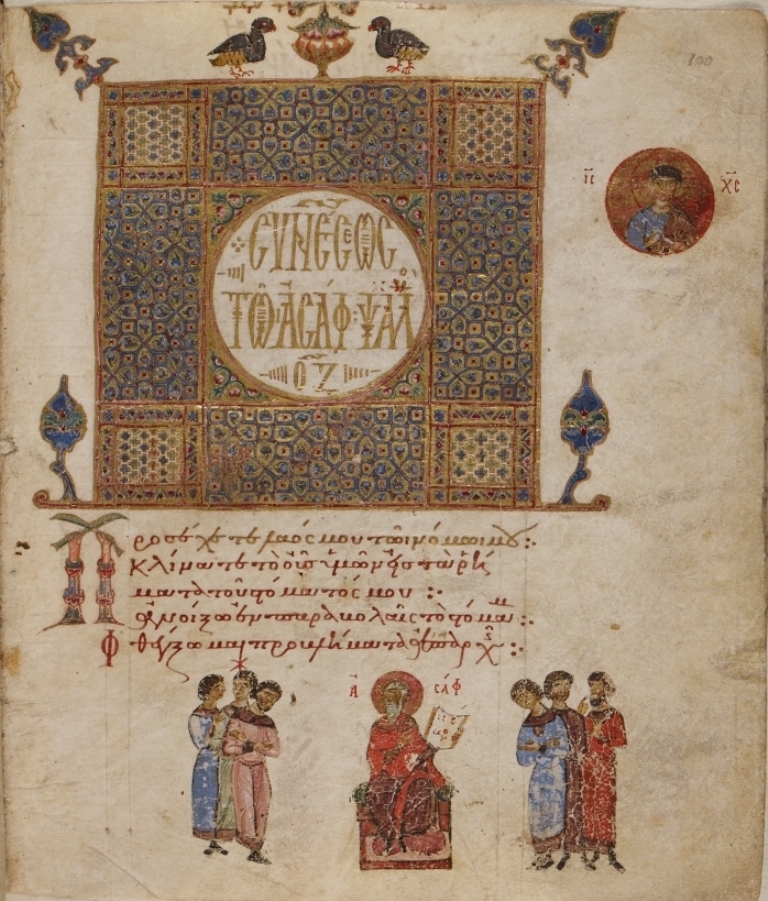

Papyri written in this form of Greek exist from as early as the fourth century BCE and continue into the ninth century. This style of writing likely evolved from the carving of letters into stone. Because such a plentiful written record exists historians know about the social, economic, and literary culture of Ancient Greece. New Testament texts were also first written in this form of Greek with fragmentary papyri dating as early as the third century CE. By the fourth century, the script used in the majority of New Testament papyri was refined to form a “biblical majuscule“. This was an elegant script with careful attention paid to the sizing and placement of the letters and allowed the biblical text to be produced in a true “literary” style. This script is best seen in the great codices of the fourth and fifth centuries, like Codex Vaticanus. A literary majuscule such as this was used for books to be read or displayed, while a more rudimentary form continued to be used for administrative documents.

From the fourth century to the ninth, the majuscule script dominated the literary landscape of Greek culture. However, as the years progressed a more “cursive” form of the script began to take shape, originating in the administrative documents of the fifth and sixth centuries. This new script was advantageous in that it allowed documents to be written with greater speed but disadvantageous in that it reduced the legibility of the text. Just as the Greek majuscule script underwent centuries of refinement before it would produce the admirable literary form of Codex Vaticanus and others, this cursive majuscule began to evolve into what would eventually become the predominant literary script for the Geek speaking world up to the era of the printing press: the Greek minuscule script.

Greek Minuscule:

While the majuscule was written in a bilinear mode, the minuscule adopted a quadrilinear format, placing letters along an imaginary baseline and extending them to the imaginary top line, but also creating forms that only reached a midline and some that extended below the baseline. It also brought with it the curious feature known as “ligatures”, wherein multiple letters are joined together in such a way as to blur their individual identity but save space on the page. Additionally, these letters were written with rounded edges and connecting lines and introduced spacing between words, though not as consistently as we might see in English texts. The majority of New Testament manuscripts are written in this style of Greek handwriting.

Early forms of these smaller, cursive letters are found in the administrative papyri, invading more and more of the page into the seventh century. By the eighth century, writing exercises for school children contain both majuscule and minuscule letters, but, just as was true of majuscule, this rudimentary minuscule was not fit for use in literary works—especially not sacred ones. The majuscule script, as it relates to the New Testament, had developed an almost sacral identity. It was the mode for transmitting holy writ and could not be usurped easily. In the ninth century, a monastery known as the Stoudios—led by its influential abbot Theodore—produced the first literary minuscule script, now known as the Stoudite minuscule. This script was used to write the oldest dated New Testament manuscript, Petrop. Gr. 219, or the “Uspenski Gospels,” in 835 CE.

This manuscript was a four-gospel codex written in a remarkably precise minuscule form without the aid of ruling lines on each page. The Stoudite scribes were renowned for their ability to write this form of script and housed a scriptorium so disciplined that identifying one scribe’s work from another’s is nearly impossible today. The introduction of the minuscule as a vehicle for the text of scripture opened the doors for its use throughout the culture. Though majuscule script was still employed for titles, introductory and conclusory comments, and even distinguishing biblical text from commentary, by the eleventh century the majuscule script had all but disappeared. The introduction of this new form of Greek writing brought with it the use of diacritical marking systems—used to distinguish pronunciation of words and separation of syllables—as well as punctuation for dividing sentences and clauses. Additionally, the first printed Greek New Testament adopted a later form of the minuscule script as its template, ligatures included.

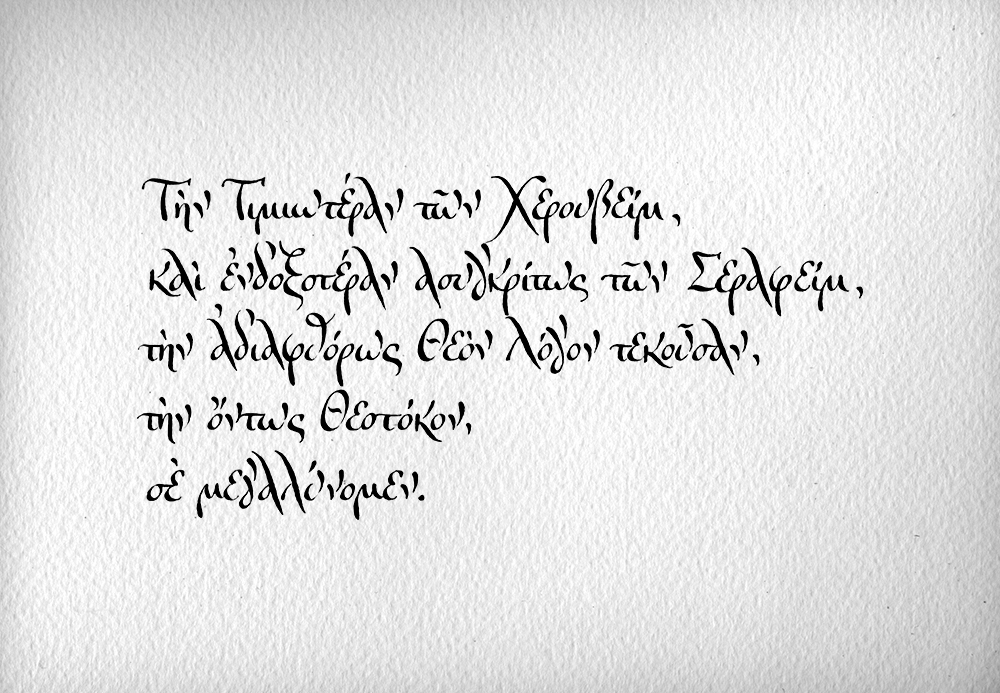

Later minuscule, 15th-century manuscript of Aristotle.

Axion estin (Greek: Ἄξιόν ἐστιν, Slavonic: Достóйно éсть, Dostóino yesť), or It is Truly Meet

Philodemus, Herculaneum Papyrus, 1005, 4.9–14

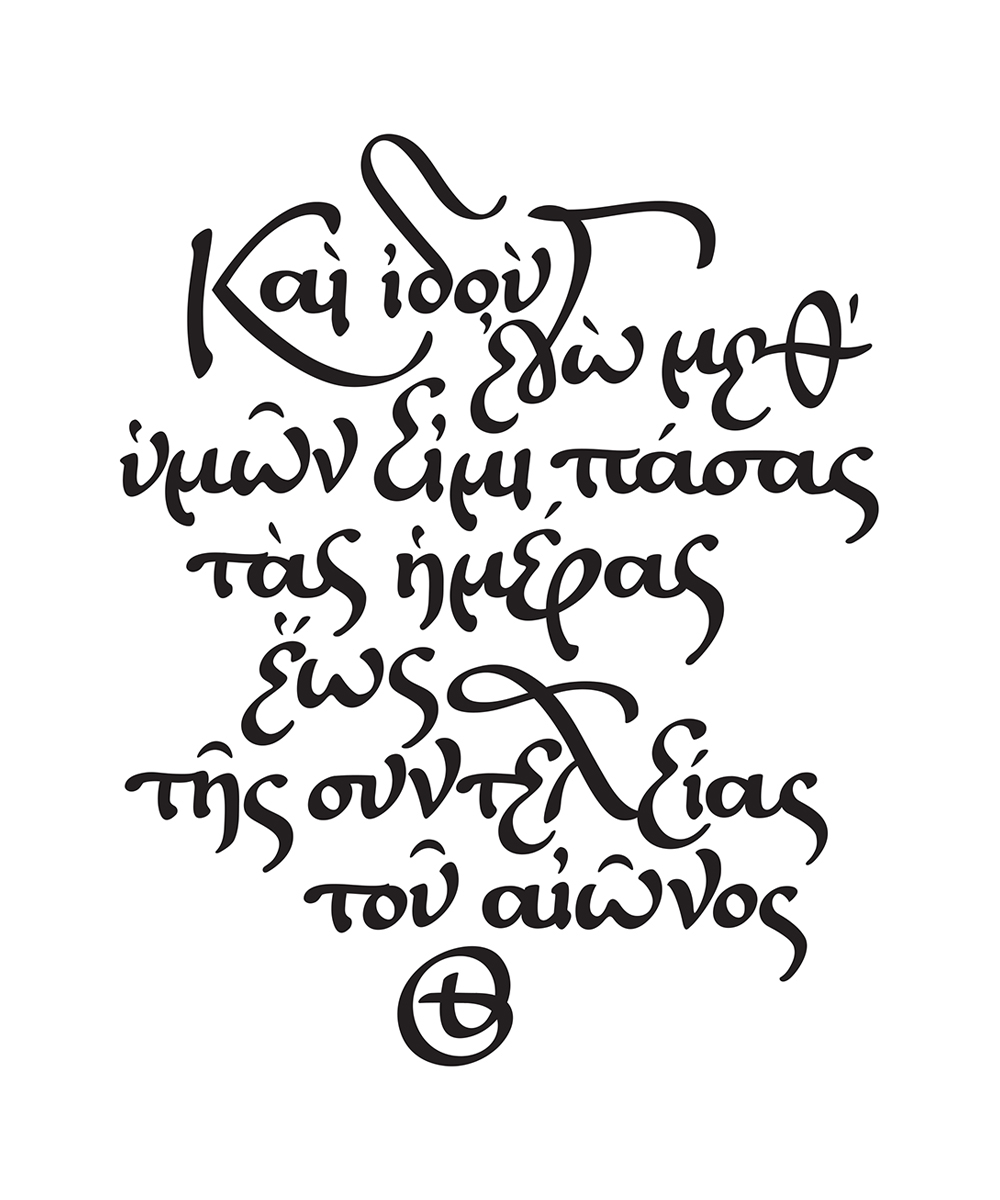

I am with you each and every day until the end of the age (Matthew 28:20)